Why Endangered Animals in the Philippines Need Your Help Now [2025 Guide]

The Philippines stands fourth worldwide with 384 threatened animal species facing extinction. This beautiful island nation’s wildlife is disappearing faster than ever, and more than 700 native species now face serious risks. These endangered animals are losing their battle against habitat destruction, poaching, and human interference.

The country’s iconic wildlife faces unprecedented challenges. Take the majestic Philippine eagle – its population has crashed from 6,000 birds just forty years ago to fewer than 100 today. The story of the Tamaraw buffalo shows a similar pattern. Their numbers fell drastically from 10,000 in 1900 to just 100 in 1969. Thanks to conservation work, their population has grown to about 480 now. The Philippine crocodile’s situation remains critical – it’s now the world’s rarest crocodile species with only 92-137 mature individuals left.

The situation becomes even more concerning when you realize many of these rare animals don’t exist anywhere else on Earth. The country’s wildlife uniqueness is striking – 67% of its 180 mammal species live only in the Philippines. Without immediate action, these animals will vanish forever. This piece explains the critical state of the Philippines’ unique wildlife, current conservation efforts, and ways you can help ensure their survival.

The Philippines: A Biodiversity Hotspot

The Philippines boasts an incredible wealth of life. This tropical archipelago is home to more than 52,177 described species (Biodiversity Management Bureau), and half of these species exist nowhere else on Earth. The uniqueness of its wildlife makes this island nation truly special.

Why the Philippines is home to rare animals

The Philippines ranks among seventeen megadiverse countries globally and stands as a recognized biodiversity hotspot. This rich concentration of life comes from the country’s distinct geography and history.

More than 7,600 islands create ideal conditions for species to develop in isolation. Animals and plants on different islands slowly develop unique traits and become new species. Scientists call this process “speciation”. This explains why so many endemic animals—creatures unique to this region—call the Philippines home.

The statistics paint an amazing picture. The Philippines has 1,238 terrestrial vertebrate species, and 618 (50%) of them are endemic, that means, they don’t exist anywhwew else, just in the Philippines. This high rate of endemism shows up in animal groups of all types:

- 243 of 714 bird species are endemic (34%), making the Philippines third globally in endemic bird count

- 207 land mammals live here, and over 100 (61%) are endemic

- 85% of nearly 90 amphibian species live only in these islands

- 68% of the country’s 235 reptile species exist nowhere else

The marine life is just as diverse. People often call the waters around the Philippines “the center of the center” of biodiversity. These waters are home to about 3,214 fish species. The Verde Island Passage alone contains more than half of all known fish species worldwide.

Verde Island Passage:

What makes island ecosystems vulnerable

The Philippines’ remarkable wildlife faces serious threats. Island ecosystems are fragile for several reasons.

Limited space poses a major challenge. Animals have nowhere to go when forests disappear. The Philippines has lost much of its original forest cover. Endemic species now survive in smaller and smaller habitats. The Philippine eagle shows this problem clearly—it can only breed in primary lowland rain forest, which barely exists in the country now.

Island animals often develop without natural predators or competition. New species introduced by humans can destroy the balance. Lake Lanao in Mindanao tells this sad story—almost all native fish species have vanished because people introduced tilapia for fishing.

Small populations restricted to specific areas make island species easy targets for threats like disease. The tamaraw, a dwarf buffalo native to Mindoro Island, has seen its numbers drop in part from diseases spread by cattle and livestock.

Many Filipinos don’t know these unique animals exist only in their country. A conservation document states it clearly: “To Educate The Filipino’s, That We Have Species That Nowhere Else Could Be Seen But Only In The Philippines“.

These rare animals might disappear forever without focused conservation efforts—not just from the Philippines, but from Earth itself.

The Philippine Eagle: A National Symbol

Image: Many thanks to Birdfact – birdfact.com

The Philippine eagle rules the rainforests of the Philippines as both a national symbol and a stark warning of what we might lose without immediate action to save it. The country made it their national bird in 1995, yet this critically endangered raptor faces a grim future with fewer than 400 breeding pairs (as of Philippine Eagle Foundation) remaining in the wild.

Unique traits of the Philippine eagle

This majestic bird demands attention with its remarkable size. It stands about 3 feet tall and boasts a wingspan up to 7 feet, making it one of the world’s largest eagles in length and wing surface area. A shaggy crest of long, narrow feathers frames its face – a crown that suits its role as the forest’s ultimate predator.

Evolution has given this remarkable bird:

- Eyes of piercing blue-gray that see eight times better than humans

- A huge, curved beak that darkens at the tip and fades to bluish-gray

- Strong yellow legs with 3-inch claws built to catch prey

- Cream-white underparts that contrast with dark brown upper plumage

Philippine eagles mate for life, unlike many other raptors. These solitary and territorial birds need 4,000 to 11,000 hectares of forest to survive, based on available prey. They build their nests in large dipterocarp trees, particularly the native Lauan.

Flying lemurs make up to 90% of the eagle’s diet in some areas. Though once known as the “monkey-eating eagle,” these skilled hunters also catch civets, rodents, snakes, and other medium-sized animals.

Why their numbers are declining

Several serious threats endanger the Philippine eagle population. Habitat destruction tops the list of challenges. Protected areas cover only 32% of suitable eagle territories, which leaves their nesting grounds open to logging and development.

Hunters kill these birds at an alarming pace. Each year claims at least one Philippine eagle from shooting. Rescue teams have saved 20 eagles since 2020 – about 5 birds per year. Already in 2024, bullets have claimed four eagles. The eagles reproduce slowly, laying just one egg every two years. Each death severely impacts the species’ recovery.

The shrinking forests force eagles to search for food near human settlements. These encounters often end tragically for the birds. Other dangers include accidental trapping, diseases from domestic animals, and breeding disruption from noise.

Captive breeding and forest protection

Conservation work targets two main areas: breeding programs and habitat protection. The Philippine Eagle Foundation (PEF) runs the Philippine Eagle Center, which has bred 29 eagles since 1992. Their programs use natural pairing and cooperative artificial insemination.

The PEF has started building a new Philippine Eagle Conservation and Breeding Sanctuary in Barangay Eden, Davao City. This 13-hectare facility will offer natural breeding advantages through its elevation, vegetation, and temperature. Experts believe it could boost production from one bird every 2-3 years to 1-2 eaglets annually.

Local communities play a vital role in forest protection initiatives. The PEF promotes “Culture-Based Conservation” by working with indigenous peoples like the Lumad. Their “Bantay Bukid” program teaches indigenous partners to watch nests and report threats.

A bold reforestation project aims to plant three million native trees in critical watersheds and eagle territories. The focus lies on endemic species like narra and lauan that eagles need for nesting.

Saving each Philippine eagle means more than protecting a single species – it preserves entire forest ecosystems. These apex predators control other animal populations and shield countless species that share their forest home.

Tamaraw: The Fierce Dwarf Buffalo of Mindoro

The tamaraw, one of Earth’s rarest bovines, prowls the mountains of Mindoro Island. This fierce dwarf buffalo stands just over a meter tall at the shoulder and has become a national treasure among endangered animals in the Philippines. The population has crashed from about 10,000 in the early 1900s to just 480 of these magnificent creatures today (Re:wild – rewild.org), making them a critically endangered symbol of Philippine wildlife.

Habitat and behavior of the tamaraw

These remarkable animals once roamed all of Mindoro from sea level up to mountains 2,000 meters high. As human settlements grew, they retreated to remote mountain areas. Now they live mainly in tropical highland forests, thick brush near open-canopied glades, and grassy plains close to water sources.

Unlike their water buffalo cousins, tamaraws prefer to be alone. Adult males live solitary lives and tend to be aggressive, while females stay with their young of different ages. On top of that, these animals have learned to avoid human contact. Though they used to be active during daylight, many tamaraws now come out at night – a survival strategy that shows their ability to adapt.

These animals love to wallow in mud to control their body temperature and keep insects away. They feed mostly on grasses and have a special liking for cogon grass and wild sugarcane. The sort of thing I love about their social structure is that young tamaraws gather in small groups to establish pecking order, while adults keep to themselves.

Threats from disease and habitat loss

Several threats caused the tamaraw’s dramatic decline. The rinderpest epidemic of the 1930s hit hardest and devastated the thriving population. This cattle plague came from non-native livestock and showed how easily island species can fall to foreign diseases.

Today’s tamaraws face these critical threats:

- Habitat destruction from infrastructure development, logging, and agriculture

- Hunting and poaching for meat, both for sport and survival

- Diseases spreading from domestic cattle and water buffalo

- Limited space as human pressure restricts their movement and growth

Farming and cattle ranching have caused the most damage. Slash-and-burn farming has destroyed grasslands and forests, split up tamaraw groups, and limited their food and shelter. Ranching has also created competition for grazing land.

Conservation efforts in Mt. Iglit-Baco

Mt. Iglit-Baco National Park protects about 80% of all remaining tamaraws. The park started as a game refuge and bird sanctuary specifically to save this native species.

Conservation work shows promise. The Tamaraw Conservation Program (TCP), a 1979 Presidential Order, has helped grow numbers from 154 in 2000 to roughly 480 today. Rangers from this special unit of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources guard the mountainous terrain from poachers.

Recent findings have given conservationists new hope. Small tamaraw groups live beyond Mt. Iglit-Baco in the Upper Amanay Ranges and Aruyan-Malate Critical Habitat. Better yet, these groups include calves and newborns, proving they’re still breeding.

The National Tamaraw Conservation Action Plan looks toward a bright future. By 2050, it aims to help tamaraws thrive in well-managed habitats across Mindoro while living alongside indigenous communities. This plan recognizes that saving these animals needs partnership with the Mangyan indigenous people who share the tamaraws’ homeland.

The tamaraw’s survival, like many endangered Philippine animals, depends on finding balance between conservation and indigenous rights. These fierce dwarf buffalos can only be saved through true partnership.

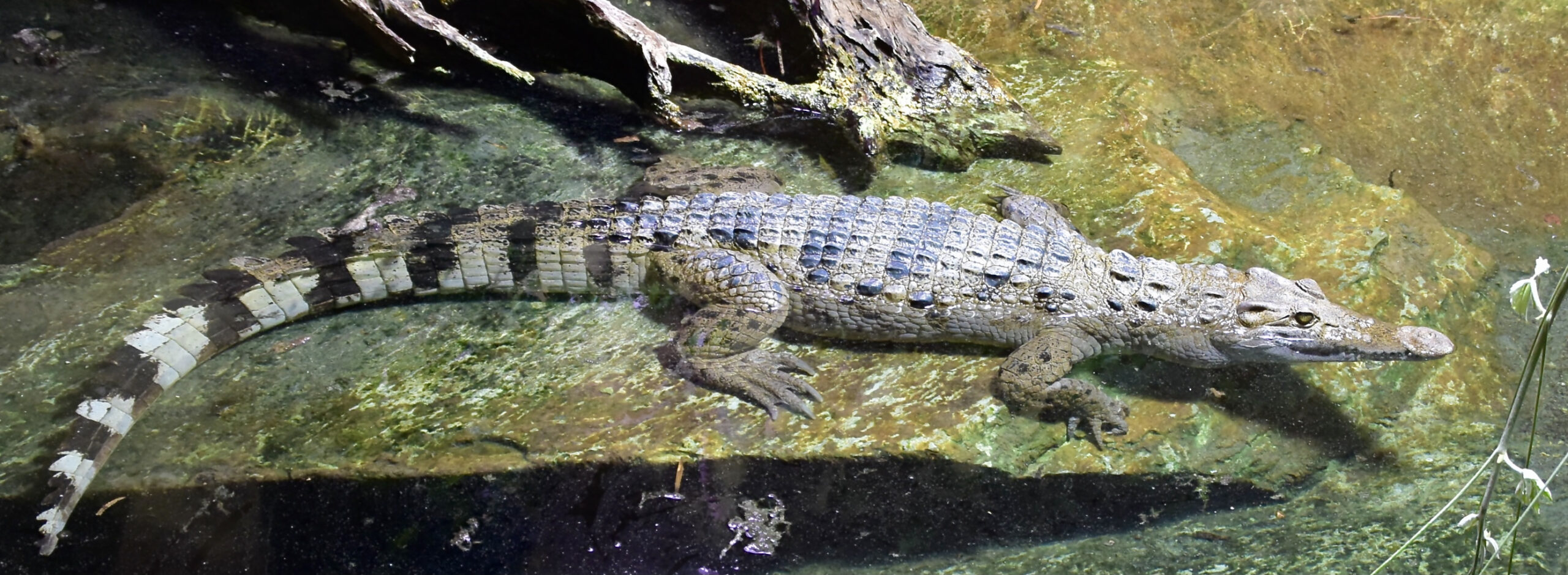

Philippine Crocodile: The World’s Rarest Croc

Critically Endangered Status:

- The Philippine Crocodile is considered one of the most severely threatened crocodile species in the world.

- It has been classified as Critically Endangered by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) since 1996 (and earlier as endangered from 1982 to 1996).

- Population estimates are alarming, with fewer than 100 mature adults remaining in the wild by some accounts (ranging from 92 to 137, or even fewer than 100 non-hatchlings). Its numbers are estimated to have fallen by 85-94% between 1937 and 2012.

Distinguishing Characteristics:

- It is endemic to the Philippines, meaning it is found nowhere else on Earth.

- It is a relatively small freshwater crocodile, with males typically growing up to 3 meters (10 feet) long, and females being smaller. This contrasts significantly with the larger Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), also found in the Philippines.

- They have a broad snout and heavy dorsal armor (thick bony plates on their back).

- Young crocodiles are golden brown with dark stripes, while adults are brown and gray with black markings.

Habitat and Diet:

- Philippine crocodiles primarily inhabit freshwater rivers, ponds, marshes, and even man-made reservoirs. They have also been found in mountainous regions in rivers with rapids.

- Their diet includes fish, aquatic invertebrates (like snails and shrimp), small mammals, other reptiles, and some birds. Notably, snails make up a significant portion of their diet, including the invasive golden apple snails, which helps local farmers.

Threats to Survival:

- Habitat loss and degradation are primary threats, largely due to human population expansion and conversion of wetlands for agriculture.

- Hunting and persecution by local communities due to fear or for their meat and hides have historically been, and continue to be, a major issue. Many people view them as dangerous, though in reality, they are not aggressive unless provoked.

- Unsustainable fishing methods, such as dynamite fishing, can accidentally kill crocodiles.

- Low hatchling survival rates in the wild also contribute to population decline.

- Geographically isolated populations lead to decreased genetic diversity, further impacting their long-term survival.

Conservation Efforts:

- Various organizations, notably the Mabuwaya Foundation, are actively involved in conservation. Their work includes:

- Community-based conservation: Engaging local populations to change perceptions, establish crocodile sanctuaries, and reduce killings.

- “Head-starting” programs: Collecting eggs, rearing hatchlings in captivity for 18-24 months to increase their survival rate (from an estimated 5% in the wild to around 80% for released juveniles), and then releasing them into protected habitats.

- Habitat restoration and protection.

- Education and awareness campaigns in schools and communities.

- There are also captive breeding programs in the Philippines and internationally, aimed at increasing numbers for potential reintroduction.

- The Philippine government has laws protecting the species, with penalties for killing Philippine Crocodiles.

Tarsiers and Other Endemic Species at Risk

The Philippine tarsier, one of the world’s most peculiar and endangered primates, makes its home in the dense forests of the Philippines. These tiny creatures stand just 85-160mm tall, no bigger than an adult’s fist. They serve as remarkable symbols of the country’s threatened wildlife treasures. Their huge eyes and nighttime habits make them just one example of the amazing species native to this island nation.

Tarsiers and their ultrasonic calls

The Philippine tarsier (Carlito syrichta) might seem small and unremarkable, but these tiny primates have an amazing secret – they talk using ultrasonic frequencies. Scientists found that there was something unusual happening when tarsiers opened their mouths as if calling, yet humans couldn’t hear a sound.

Research teams using special equipment learned that tarsiers make calls at around 70 kilohertz and can hear sounds up to 91 kilohertz. This is a big deal as it means that their vocal range goes way beyond human hearing (which stops at 20 kilohertz) and exceeds what other primates can achieve.

These ultrasonic abilities serve two vital purposes. Tarsiers can quietly coordinate with their family without catching predators’ attention. Their high-frequency hearing also helps them track down insects that communicate at similar frequencies.

These unique primates have other remarkable features:

- Their eyes are bigger than their brain, giving them amazing night vision

- Their ankle bones (“tarsals”) are so long they inspired the animal’s name

- They can turn their head 180 degrees since their eyes don’t move

- They jump up to 40 times their body length

The Philippine tarsier population continues to shrink. Their survival faces threats from habitat loss, stronger typhoons caused by climate change, and human activities.

Other animals found only in the Philippines

The Philippines boasts an incredible variety of unique species beyond tarsiers. Scientists have identified 52,177 species here, and about half live nowhere else on Earth.

Land-based vertebrates tell an impressive story – 618 of the country’s 1,238 species (50%) are unique to these islands. Bird diversity stands out even more. The Philippines has 714 bird species, and 243 of them are found only here. This puts the country third globally for unique birds, right behind Australia and Indonesia.

The most endangered native birds include:

- The Sulu hornbill, with only 27 birds left in the wild

- The Calayan rail, rated as the world’s most threatened rail species

- Tawi-Tawi’s Blue-Winged Racket-tail, Southeast Asia’s rarest parrot

The Zoological Society of London ranks the Philippines first worldwide for bird uniqueness. Six of Earth’s 50 most distinct and endangered species call these islands home.

How tourism can help or harm

Tourism creates both benefits and risks for Philippine wildlife, especially tarsiers. Bohol has made tarsiers its tourism symbols, but this spotlight brings serious challenges.

Roadside attractions often keep tarsiers in poor conditions. These sensitive animals can die from tourist-related stress – some even stop eating or hurt themselves fatally when traumatized.

The Philippine Tarsier Foundation offers a better way. Since 1996, this sanctuary has taught visitors the right way to observe tarsiers. Small guided groups ensure these delicate creatures stay peaceful.

Smart tourism practices can fund vital conservation work. Visitors to well-run facilities support habitat protection, research, and community education. Bad tourism practices often feed the illegal pet trade as tourists try to buy animals they see.

Finding the right balance remains challenging. Tourism raises awareness and provides resources but needs careful management to protect the wildlife people come to see. The success of endangered species conservation in the Philippines often depends on educating visitors and implementing proper management strategies.

The Role of Local Communities in Wildlife Protection

Throughout the Philippines, local communities stand as frontline defenders of the country’s remarkable biodiversity. These nature’s stewards work tirelessly to protect endangered species. They blend traditional wisdom with modern science in their innovative conservation work.

Community-based conservation programs

Community involvement is at the heart of successful wildlife protection efforts throughout the Philippines. Twenty-three community-based organizations received PHP 100 million in grants under the Global Environment Facility Small Grants Program (SGP-7) in 2023. These grants support conservation initiatives that range from biodiversity protection to sustainable agriculture and ecotourism. The benefits of these programs go way beyond immediate conservation goals. The project will directly help about 20,000 people, while an estimated 300,000 will benefit indirectly across four project sites. This shows how community-centered approaches can create widespread positive change.

Conservation International Philippines shows how this works by collaborating with local populations. Their programs help communities see how their livelihoods connect to nature’s health. They don’t impose external solutions. Instead, they train people in sustainable livelihoods that help them move away from unsustainable—and often illegal—activities.

In practice, these initiatives take various forms:

- Community patrols where trained locals conduct on-the-ground surveillance

- Alternative livelihood schemes providing additional income to reduce pressure on forest resources

- Locally-managed marine protected areas that allow fish populations to recover

- Youth education programs creating “hyper-awareness” of conservation issues

The Philippines Biodiversity Conservation Foundation puts it well: “There is no such thing as a conservation problem; it’s a people problem”. This viewpoint acknowledges that saving endangered animals requires addressing human needs first.

How You Can Help Save Philippine Wildlife

Making a difference for the Philippines’ unique wildlife doesn’t require a trip there. You can help these remarkable creatures thrive right from your home or as a visitor.

Support local conservation groups

Dedicated organizations protect endangered animals in the Philippines every day. HARIBON Foundation helps people turn their daily routines into meaningful environmental actions and offers biodiversity-friendly activities for special events. Conservation International Philippines shows communities how their livelihoods connect to nature’s health, which creates better alternatives to harmful practices. The Philippine Eagle Foundation saves the national bird through research, education, and breeding programs.

Visit eco-parks and sanctuaries responsibly

The Philippines’ ecotourism has grown into a big deal as the country highlights its natural attractions while focusing on environmental responsibility. Your visits to places like the Masungi Georeserve in Rizal, with its 400 species of animals, or Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park in Palawan directly support conservation efforts. These sanctuaries provide guided experiences that teach visitors while protecting wildlife. Responsible tourism lets you enjoy breathtaking experiences without harming the ecosystems you came to see.

Donate or volunteer for wildlife programs

Here are some great ways to get involved hands-on:

- The Philippine Eagle Foundation welcomes volunteers (ages 13+) to help with education, research, or special events programs

- Marine Conservation Philippines needs scientific divers to document coral reef health

- Project Curma’s sea turtle rescue lets volunteers release thousands of baby turtles during hatching season

- IVHQ’s Environmental project in Palawan helps rehabilitate vital mangrove habitats

Small donations can make a real impact, and many organizations accept international support through various payment methods.

Avoid buying exotic pets or wildlife products

The illegal wildlife trade in the Philippines reaches ₱50 billion annually (approximately USD 1 billion). This devastating industry threatens native species and reduces biodiversity. Republic Act No. 9147 punishes illegal wildlife trading with jail terms up to two years and fines up to P200,000. Wildlife trafficking links to zoonotic diseases that can trigger global pandemics—another good reason to skip exotic pets or wildlife products. You can appreciate these animals in their natural habitats or through wildlife photography instead.

Conclusion

The Philippine archipelago’s natural wonders face threats like never before. Unique species found only in these islands fight to survive each day. Hundreds of native creatures stand at extinction’s edge, yet hope shines through dedicated conservation work and rising public awareness.

Protection efforts for iconic species such as the Philippine eagle, tamaraw, and tarsiers safeguard entire ecosystems. Rangers watch over distant forests while breeding centers work to boost population numbers. Local communities have become vital partners in these protection efforts by combining their traditional ecological knowledge with modern conservation approaches.

Your actions can make a real difference for these endangered animals. A simple visit to eco-parks or support for local conservation groups creates lasting effects throughout ecosystems. The text also helps curb the illegal wildlife trade valued at approximately $1 billion annually when you avoid wildlife products and teach others about these remarkable creatures.

Time works against these species without doubt. Many unique Philippine animals could vanish forever in our lifetime without swift action. Climate change speeds up these threats, especially when you have coastal and marine ecosystems that shape this island nation.

Philippine biodiversity’s loss would harm not just ecosystems but also the nation’s cultural legacy, tourism future, and food security. Notwithstanding that, every conservation victory shows what determined action can accomplish.

These endangered animals showcase millions of years of adaptation to their island homes. Their future rests in our hands today. The Philippines’ unique wildlife still has a chance to flourish for future generations through united efforts of governments, communities, organizations, and individuals.

FAQs

Q1. What are the most critically endangered species in the Philippines as of 2025?

The Philippine government has identified six priority species for conservation efforts due to their critically endangered status: the Philippine eagle, marine turtles, dugong, Philippine cockatoo, tamaraw, and the Philippine pangolin. These species face severe threats from habitat loss, poaching, and climate change.

Q2. How many endangered animals are there in the Philippines?

Currently, up to 2,000 of the 56,000 species of flora and fauna in the Philippines are considered critically endangered and vulnerable to extinction. This includes a wide range of animals from various habitats, including forests, mountains, and marine ecosystems.

Q3. What is the main threat to wildlife in the Philippines?

The destruction of habitats is the greatest threat to Philippine wildlife. This is caused by a combination of factors including deforestation, climate change, human activities, and natural disasters. The loss of natural habitats forces many species into increasingly smaller areas, making them more vulnerable to extinction.

Q4. How can tourists help protect endangered species in the Philippines?

Tourists can help by visiting eco-parks and sanctuaries responsibly, supporting local conservation groups, and avoiding the purchase of exotic pets or wildlife products. Responsible tourism practices allow visitors to enjoy wildlife experiences while contributing to conservation efforts and local economies.

Q5. What role do local communities play in wildlife conservation in the Philippines?

Local communities, especially indigenous peoples, play a crucial role in wildlife protection. They act as frontline defenders of biodiversity, often incorporating traditional knowledge into conservation efforts. Community-based conservation programs have proven effective in protecting habitats, conducting wildlife patrols, and developing sustainable livelihoods that reduce pressure on natural resources.

2000 Philippine species critically endangered – DENR

Manila Bulletin: World Wildlife Day: Protect PH natural treasures

Best Philippines Diving Sites: From Beginner to Pro in 2025

Unpacking the Philippines’ Climate

Any Questions?

If you have any questions, please use the contact form. I will be happy to answer them.